ゼミの紹介

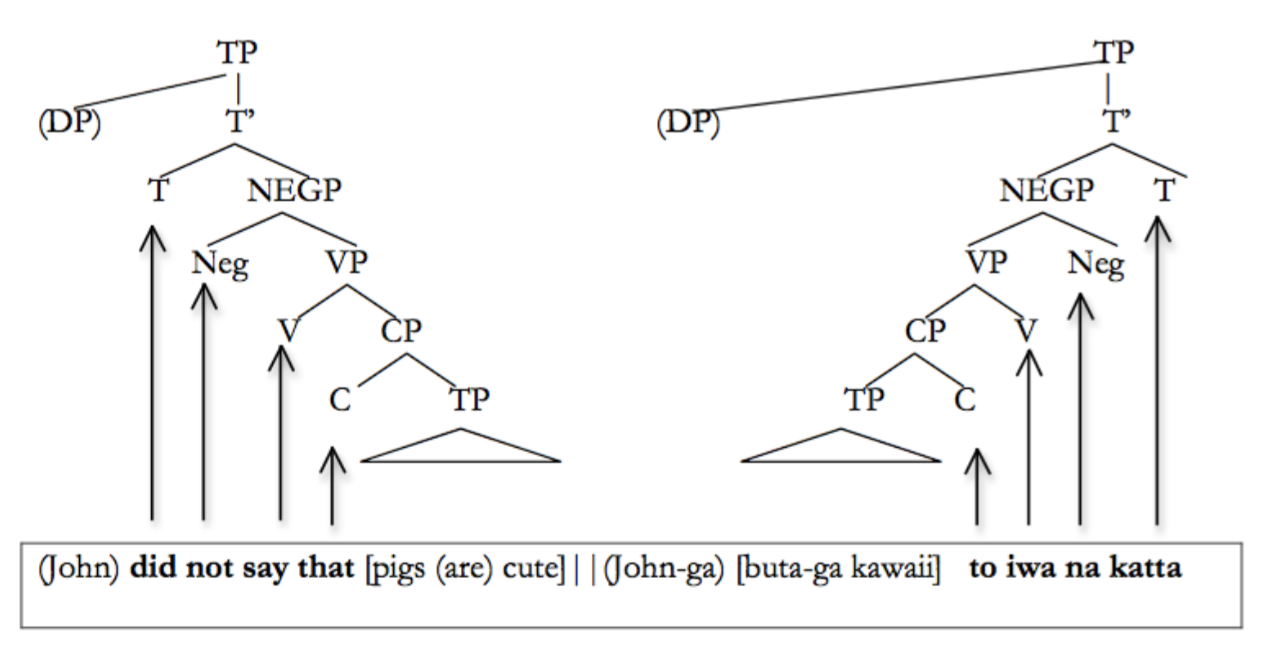

This year’s Zemi class will be concerned with comparative syntax: understanding the similarities and differences between English and Japanese. In contrast to what you might have learned in English language classes, this class will not focus on different phrases or expressions in two languages, but on the abstract theory and acquisition of syntax: what speakers know about their native language, and how they come to know it. A lot of what Japanese speakers know about Japanese is similar to what English speakers know about English, but that’s not what you typically notice: we notice the obvious differences (but not the subtle ones). An obvious example of this is basic word-order: in English, the object follows the verb (VO eat the pizza), in Japanese, the verb follows the object (pizza-o taberu OV). In fact, this is part of a larger pattern: in Japanese, post-positions follow their complement (Pari-de, NP-P), in English prepositions precede the verb (in Paris) P-NP; in Japanese, complement clauses precede the main verb (CP-V) in English, it follows. See the figure below. Overall, then Japanese is a HEAD-FINAL LANGUAGE, while English is a HEAD-INITIAL ONE:

In one way, this seems like a huge grammatical difference, because it means that long sentences are very hard to understand and to produce: the word-order of English and Japanese is completely hantai. But in another respect, the grammar is exactly the same: if you look from the top-down, or from the bottom-up, instead of from left to right, the hierarchical relations are identical. So what seem to be big differences can be quite unimportant.

On the other hand, there are many less obvious grammatical differences that are actually more significant, because it’s harder to see how they can be learned. To cite just two examples, consider how you might translate the sentences in (1) and (2) into English:

(1) a.

Emma-wa Mary-ni jibun ni tsuite omosiroi koto-o hanasita.

Emma-TOP Mary-DAT self about interesting something-ACC tell-PAST

(1) b.

Emma-wa Mary-ni jibun-no yume ni tsuite hanasita.

Emma-TOP Mary-DAT self-GEN dream about tell-PAST

(2) a.

michi-o (hashitte) agatteiru

street-ACC (run-INF) climb-PROG

(2) b.

saka-o (hashitte) nobotteiru

slope-ACC (run-INF) climb-PROG

It turns out that is no direct translation is possible for any of these sentences, and that the translations that are possible have slightly different interpretations from the originals. For example, (3a) is a possible translation of (1a)—but (3a) is ambiguous whereas (1a) is not; (3b) is a good translation of (2b), but necessarily focuses on a different aspect of the event (running, not climbing).

(3) a. Emma told Mary something interesting about herself. (3) b. She is running up that hill.

In the Zemi, we’ll focus on two questions: (i) what do we know when we know the grammar and interpretation of the expressions in (1) and (2); how do we learn these facts? (Nobody teaches us about interpretation, yet they vary from one language to another, so we must learn them somehow).

The content of the Zemi will assume the content of English Grammar I/II. You don’t need to have taken this class, but it will certainly help if you have.

ゼミの進め方

The language of the seminar is ENGLISH. You will be expected to read materials, to ask questions, to make presentations—and to write your senior thesis!—in English. For most of you, this will be a great challenge, but if you start early, by participating and writing homework assignments in English, it should become easier.

これまでの卒論テーマ

その他

担当者の関心

Linguistic relativity, language acquisition, language & cognition, Vietnamese grammar. See my website for details: https://ngduffield.wix.com/home