図書館報『藤棚ONLINE』

マネジメント創造学部・中村聡一先生 コラム 「リンカーン」

学生の皆さん。

西宮キャンパスの中村聡一と申します。

平穏な時代が長きにわたり続きましたが、国際社会は今戦争のリスクにさらされています。

羅針盤になる価値観は永遠に不滅です。それは、”正義”です。

アメリカの分裂危機を救ったリンカーンを紹介します。

………………

エイブラハム・リンカーン

リンカーン「分かたる家は立つこと能わず演説」「リンカーン・ダグラス論争」「クー パー・インスティティテュト演説」「ゲティスバーグ演説」

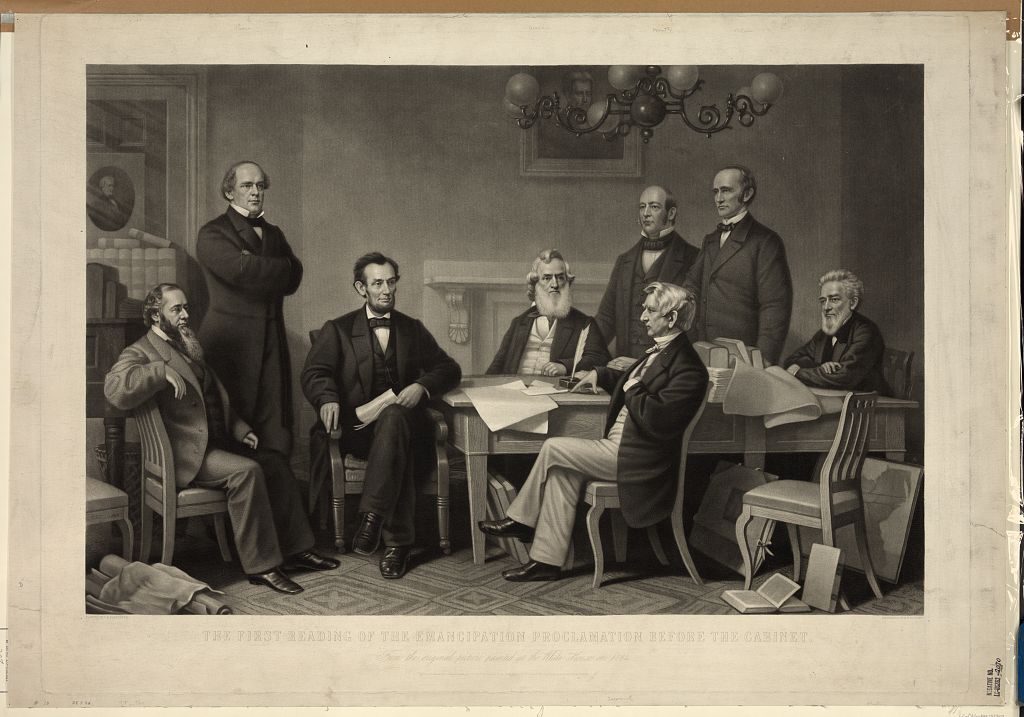

(内閣における奴隷解放宣言の最初の朗読)

Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress(米国議会図書館)より

合衆国の大統領として奴隷解放にあたったリンカーンは、敬虔なキリスト教信者である。

恵まれない移民の境遇から独学で身を興した。

真実の人として知られる。

”I am nothing but truth.”

彼自身の言明である。

建国からほぼ1世紀を経たが、19世後半に至っても自由の国アメリカは厄介な問題には蓋をしてきた。

奴隷制だ。

南部の経済は奴隷制をもっての大規模農園が主体であった。理念以上に実利が優先された。

自由憲法も、この問題には狡猾な解釈がなされる。

「奴隷は所用者の財産であって、憲法の適用範囲外である。」

南部で行われていることは南部の問題であり、合衆国政府としては関与したくない。

いわゆる無関心政策だ。

しかしパッチワークには必ずほころびが生じる。

南部の奴隷州から黒人奴隷が脱走してきたとする。

北部の自由州では奴隷制は認められていない。だから、もはや奴隷ではない。

しかし南部の奴隷の所用者は州政府を通じて、その奴隷の引き渡しを要求する。

放置すれば奴隷の大量脱走が生じる。南部諸州の没落につながる。

法の理念に照らして、引き渡すべきか、否か。

連邦政府としても無関心で通せなくなる。大いなる議論を招く。

南部諸州は、引き渡しは正当な財産の保全であると当然に主張する。

対して、それを認めれば、自由州を含めて、合衆国すべてが奴隷制を追認することになる。

煮え切らない対応に、南部諸州は、合衆国からの脱退も辞さない。大量脱走を食い止めるには自由州とのあいだに国境を作り出すしかない。

連邦政府が阻止するなら戦争も辞さない。

どちらつかずの対応に限界がきた。

「分かれたる家は立つこと能わず」

正と不正のあいだの中間的な立場を模索するというような計略は破綻した。そんなことは「生きてもいない、死んでもいない人間」を探すのと同じだ。

誰もが思うが誰も決して公には発言しない。

リンカーンが言明した。

「黒人を人間と思わず、野の禽獣と扱うとき、こうして呼び起こされた悪霊は、やがて逆に汝自身を裂き破るのではないか。アメリカの自由と独立との城壁をなすのはなにか。軍艦や軍隊ではない。われらの胸底に神が給うた自由を愛する心である。」

すべての人に天与の自由を愛する心。そして互いのそれを尊ぶ精神。

他人の権利を平気で蹂躙する。それは、すなわち、自分たちの独立の精神(本性)をも失することだ。

「正義は力であるとの信念を持ち、この信念にたってわれらの義務とするところを敢然と最後まで果たそうではないか。」

大統領に選出される。

南北戦争の決戦の場となったゲティスバーグにての戦没者追悼の式典。

「87年前、われらの父祖たちは、自由の精神にはぐくまれ、すべての人は平等につくられているとの信条に捧げられた、新しい国家を、この大陸に打ち建てた。」

「この国家が、この精神が、永続できるか否かの試練を受けている。」

「人民の人民による人民のための政治を地上から決して絶滅させないために、我々がここで固く決意することである。」

真実を語る政治家として世界史に永遠に輝く事業をなした。

しかし、大統領2期目の就任直後、凶弾によって死を迎える。

………………

リンカーンの演説は私の新刊書に収録されています。年明け1月に発売になります。Amazonで予約注文もできます。

『「正議論」講義~世界名著から考える西洋哲学の根源』

https://www.amazon.co.jp/o/ASIN/4492212531/toyokeizcojp-22/

………………

(紹介文)

NYコロンビア大学で100年以上の歴史を誇る名物哲学授業を徹底的に研究。そこから導きだした古くて新しい「正義論」を、古代ギリシャの哲学者プラトンとアリストテレスの対話形式で紹介する。

米国エリート教育の原点がここにある!

………………

(東洋経済ONLINE)

戦争、分断、格差…「力」の前に「正義」は無力なのか | リーダーシップ・教養・資格・スキル | 東洋経済オンライン | 社会をよくする経済ニュース (toyokeizai.net)